Orion and Eridanus

Eridanus is one of the largest and most elusive constellations of the winter sky. Beginning near the bright star Rigel in Orion, it unfolds as a long, sinuous chain of faint stars that early observers naturally perceived as a river flowing from the heavens toward the horizon. Unlike compact constellations, Eridanus is experienced sequentially: the eye follows it downward, star by star, reinforcing the impression of movement rather than form. This visual quality made Eridanus especially suitable for mythic interpretation as a cosmic watercourse (McCluskey 1998; West 2007).

In the Negev Desert, where seasonal wadis briefly come alive after winter rains, the idea of a celestial river carried immediate experiential meaning. The sky was not an abstract dome but an active landscape mirroring the rhythms of survival below. Rock art scenes that combine Orion with a descending curved line echo this perception, transforming astronomical observation into a symbolic narrative of flow, descent, and cosmic consequence.

Across Egypt, Greece, Mesopotamia, and Bronze Age Europe, Orion is repeatedly paired with a celestial river or watery descent, whether named Eridanus, Nile, Apsû, or night sea, suggesting a shared cosmological logic in which stellar order is defined against the risk of uncontrolled flow.

Orion–Eridanus as Astronomical Structure

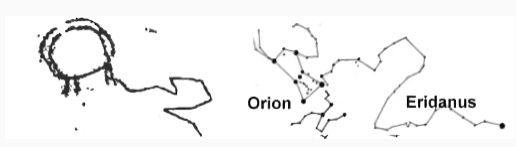

In Fig. 1, Negev rock art renders this celestial relationship with striking economy. The familiar ibex, the established analogue for Orion, stands above a sweeping curved line, that descends from Orion tracing the path of the constellation Eridanus that begins in the star Rigel and flowing southward beyond the horizon.

What is particularly noteworthy is the absence of intermediate figures. The engraver resisted narrative clutter, choosing instead a minimalist syntax: constellation above, river below. This compositional clarity suggests deliberate astronomical intent rather than symbolic improvisation. Similar reductions appear in other Negev panels, where complex celestial systems are condensed into a small number of essential signs.

Orion and Eridanus Myth

In Greek tradition, Eridanus is inseparable from the myth of Phaethon, the mortal son of Helios. Granted permission to drive the sun chariot for a single day, Phaethon failed to control the fiery horses. The chariot veered from its ordained course, scorching the earth, drying rivers, and transforming fertile lands into deserts. To halt the catastrophe, Zeus struck Phaethon with a thunderbolt, and the youth fell into the celestial river Eridanus, where his descent was eternally memorialized among the stars (West 2007).

This myth is not merely a cautionary tale of hubris. It encodes a sophisticated astronomical principle: the sun must adhere to a precise cosmic route. Deviation from this path threatens not only celestial order but ecological balance on earth. Comparable ideas appear in Egyptian solar theology, where the nightly journey of the sun through the underworld is fraught with danger and must be carefully guided to ensure rebirth at dawn (Assmann 2005).

Seen through this lens, the Negev Orion–Eridanus scene participates in a broader Mediterranean discourse on cosmic regulation. The river beneath Orion does not signify fertility alone; it represents consequence. Orion stands at the threshold between order and excess, mastery and collapse.

During winter surveys in the central Negev, it is striking how often Orion appears to “stand” above dry wadis that only briefly carry water after rainfall. When seen from certain engraved panels at dusk, the constellation seems to pour directly into the landscape below. Such moments suggest that ancient observers experienced the Orion–Eridanus relationship not as abstract myth but as lived cosmology, where sky and land were visually and conceptually continuous.

Conclusion: From Cosmic Balance to Cosmic Control

Early cosmologies emphasized balance: the sun followed its path, rivers flowed, and the world renewed itself through cyclical order. The Orion–Eridanus complex reflects this worldview, presenting the sky as a system that must be respected rather than dominated.

Over time, however, myth and imagery reveal a subtle but profound shift. The story of Phaethon introduces the idea that cosmic forces can be seized, misused, and catastrophically misdirected. In this transition, the role of Orion evolves from guardian of balance to regulator of power. Control replaces harmony as the central problem.

Negev rock art captures this transformation with remarkable restraint. By placing Eridanus beneath Orion, the engraver encoded a warning without narrative excess: cosmic mastery carries risk. The gods in the sky remembers every deviation.

Related reading

Bibliography

Assmann, Jan. 2005. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kaul, Flemming. 1998. Ships on Bronzes: A Study in Bronze Age Religion and Iconography. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

Kristiansen, Kristian. 2010. “The Sun, the Moon, and the Twins.” In Symbols and Archaeology, edited volume.

Kristiansen, Kristian. 2018. The Rise of Bronze Age Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCluskey, Stephen C. 1998. Astronomies and Cultures in Early Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

West, M. L. 2007. Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

© All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of negevrockart.co.il

Yehuda Rotblum