Fish and the Journey to the Afterlife

This rock art panel is exceptional in presenting the entire afterlife journey as a single, continuous process, from burial to the soul’s passage beyond the underworld. Unlike most Negev rock art, which isolates a single symbolic moment, this scene unites burial, transformation, and passage into one coherent narrative. Its importance lies in the integration of lived funerary practice with cosmological imagery, a combination rarely preserved as a single visual statement in Near Eastern traditions (Assmann 2005; Hornung 1999).

The interpretation presented here follows a deliberate method: visual elements are first described before symbolic meaning is proposed. Rock art is a compressed visual language, in which meaning arises from the relationships between motifs, their placement, orientation, and scale.

Burial Posture and Funerary Logic

Contracted or flexed burial posture refers to a funerary position in which the deceased is laid on the side with the legs bent at the knees, as depicted in the rock art scene discussed here. This posture is well attested in the Levant from the Natufian period through the Pre-Pottery Neolithic and into the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age (roughly 13,000–2,300 BCE). It is widely interpreted as a position of rest, return, or preparation for renewal rather than annihilation (Goring-Morris 2000; Kuijt 2008). Such funerary logic emphasizes bodily containment and stillness, framing death as a controlled and culturally intelligible transition. Its appearance in rock art suggests that this funerary logic was not only practiced but conceptually preserved, fixing the moment of death as a meaningful threshold rather than an end.

The Fish as the Soul Carrier

The fish motif in Negev Desert rock art captures an ancient vision of the soul’s journey through the hidden waters of the underworld. Fish swimming across a barren, waterless landscape deliberately contradict desert reality, transporting the viewer into a mythic, liminal realm associated with both danger and regeneration (Eliade 1958; West 1997).

As inhabitants of the depths, fish function as psychopomps, receiving the soul after its separation from the body and conveying it through lower and upper realms toward the heavens. Comparable roles for aquatic beings appear in Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and later Mediterranean traditions, where water crossings mark decisive thresholds in the afterlife journey (Hornung 1999; Assmann 2005).

Boats as Vehicles of Passage

Boats represent the means of movement within this liminal realm. They are used for the next and decisive stage of the journey, crossing the upper or celestial realm that lies beyond the underworld. They operate as metaphysical vehicles, carrying the sun, deities, or the souls of the deceased between realms. Comparative evidence from Egyptian funerary religion, where the solar barque traverses the Duat at night, and from other prehistoric traditions confirms that boats serve as ordered means of passage through chaotic or invisible spaces, linking the underworld with the celestial realm.

A Complete Scene of the Afterlife Journey

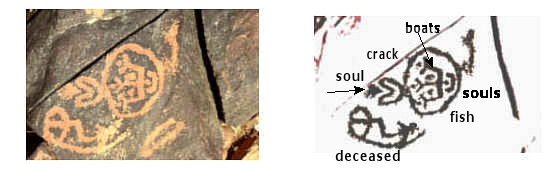

The panel is organized vertically, guiding the viewer from the physical reality of death to the mythic realm of cosmic travel. In the lower register, a human figure appears in a contracted posture closely resembling Levantine burial positions, firmly anchoring the scene in lived funerary practice. The body lies upon a curved line terminating in a loop, a visual device that emphasizes containment and the continued integrity of the corpse.

A complete afterlife journey shown as a single process: burial below, soul release, and guided passage through underworld waters above. (Photo: Razi Yahel)

Above the body, a pointed, arrowhead-like motif directs attention upward, marking marking the moment of separation between body and soul. Such directional markers are widely used in rock art to indicate transition rather than physical movement, signaling a change of state (Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2005). In the upper register, the imagery shifts decisively from the literal to the mythic: a large fish encloses two boats containing small dots, souls already in transit, situating the journey within the waters of the underworld. The boats then continue this passage into the upper world.

Conclusion

The image presents a rare and deliberate visualization of the afterlife as a process rather than a single event. The body is static and enclosed, while the soul is dynamic and mobile. This contrast reflects a conceptual division between corporeal rest and spiritual movement, a distinction fundamental to ancient afterlife beliefs across the Near East (Assmann 2005). The coexistence of realistic burial imagery with abstract, mythic transport symbols marks this scene as one of the most complete and conceptually sophisticated depictions of the afterlife journey in Negev Desert rock art, functioning as a condensed cosmological map of death, transition, and rebirth rendered in stone.

Bibliography

- Assmann, Jan. 2005. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Eliade, Mircea. 1958. Patterns in Comparative Religion. New York: Sheed & Ward.

- Goring-Morris, A. N. 2000. “The Quick and the Dead: The Social Context of Aceramic Neolithic Mortuary Practices.” In Life in Neolithic Farming Communities, edited by I. Kuijt, 103–136. New York: Kluwer.

- Hornung, Erik. 1999. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Kuijt, Ian. 2008. “The Regeneration of Life: Neolithic Structures of Symbolic Remembering.” Current Anthropology 49 (2): 171–197.

- Lewis-Williams, David, and David Pearce. 2005. Inside the Neolithic Mind. London: Thames & Hudson.

- West, M. L. 1997. The East Face of Helicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Related reading

© All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of negevrockart.co.il

Yehuda Rotblum