Introduction: The Ship/Boat Motifs from Negev Desert, Israel

This article explores the symbolic significance of ship and boat motifs in prehistoric rock art from Israel’s Negev Desert. These images are not depictions of terrestrial seafaring but expressions of deeper cosmological and eschatological beliefs. Across ancient cultures, vessels served as metaphors for the sun’s journey, the passage from life to death, and the soul’s ascent toward the celestial realm.

Egyptian funerary traditions provide a crucial comparative framework. The Coffin Texts describe the nightly voyage of the solar bark through the Duat, while the full-sized boats buried beside Khufu’s pyramid indicate that vessels were understood as real conveyances for the pharaoh’s celestial ascent. These parallels highlight how the Negev engravings participate in a wider Near Eastern symbolic vocabulary (Hornung 1999).

Cross-Cultural Parallels and Solar Cosmology

In the arid landscape of southern Israel, the ship motif functioned as a symbolic ark bearing the sun, deities, and the souls of the deceased. This iconography transcended practical maritime contexts and instead articulated ideas about cosmic order, transition, and renewal (Hornung 1999; Kaul 1998).

Comparable engravings from the Egyptian Eastern and Western Deserts show that desert‑carved boats formed part of a broader regional system of an afterlife related imagery. Ship motifs expressed movement between realms, upperworld and underworld, mortal life and divine space, rather than physical form of navigation.

Scandinavian Bronze Age scenes further illuminate and expand this afterlife vocabulary. Long boats with bird headed prows convey processional movement across both water and sky (Kaul 1998; Kristiansen 2010). Within the Negev corpus, these cross cultural analogies underscore the vessel’s role as a metaphysical medium linking earthly existence with cosmic cycles (Keel & Uehlinger 1998).

During the Late Bronze Age, Egypt exercised sustained cultural and political influence over Canaan, including the region of Israel. The Amarna Letters record the close ties between Canaanite rulers and the Egyptian court. Such interactions facilitated the spread of solar symbols, religious concepts, and royal iconography, which likely contributed to the symbolic environment in which Negev artists operated (Moran 1992; Mazar 1992; Redford 1992).

The Soul's Celestial Destination

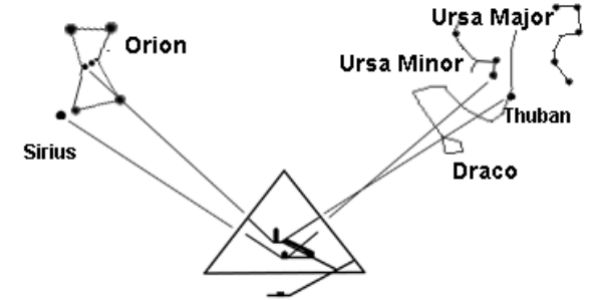

The Negev boat engravings parallel Egyptian conceptions of the soul’s journey from death to rebirth. Old Kingdom pyramid architecture (Fig.1) embodies this worldview: Khufu’s pyramid incorporates astronomically aligned shafts guiding the king’s post‑mortem ascent from the burial chamber toward Orion—the realm of Osiris—and the circumpolar “Imperishable Stars,” the eternal locus of celestial immortality (Lehner 1997; Spence 2000).

This architectural cosmology clarifies how vessels in rock art symbolized passage through darkness and return to light. Heaven was not an abstract notion but a precise astronomical destination marked by the fixed region surrounding the North Star, the only predictable unchanging place in the sky.

Ship Motifs in the Negev Desert

Seen through this comparative lens, the vessel engravings from Israel’s Negev Desert represent metaphysical concepts rather than depictions of maritime life. Their inland location, far from navigable water, reinforces their symbolic nature. Scholars of Egyptian desert art similarly interpret such imagery as representations of ideological power, cosmic order, and eschatological transition (Huyge 2002; Darnell 2009).

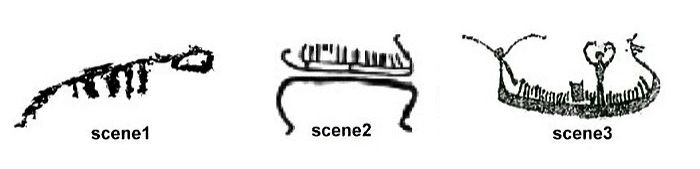

The Negev rock art (Fig.3) example (scene 1) depicts an inverted hull indicating the underworld phase of the journey. Vertical strokes inside the vessel represent the souls “shades of the deceased” (Golan 1991; Zavaroni 2006). Scandinavian and Egyptian examples reinforce the cross cultural understanding of boats as symbolic carriers of the soul.

The Egyptian solar myth in the Negev rock art

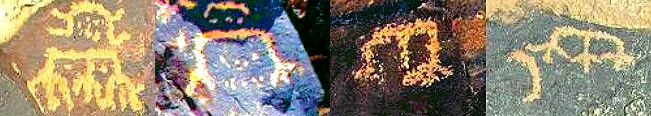

Fig. 4 presents a complex Negev rock engraving that parallels the Egyptian solar myth. According to the myth, the sun god Ra traverses the sky by day and descends into the underworld (Duat) at night, where he confronts the forces of darkness, embodied by Apophis the serpent. The left image shows the Egyptian iconographic template as recorded in a Twenty-First Dynasty depiction, while the central and right images show the Negev engraving that transposes these motifs into a local artistic idiom.

The central image in Fig. 4 presents the main part of the Negev rock engraving of this article, while the right-hand image shows the same composition with only its principal symbols. Although the upper portion of the engraving is partially eroded and therefore difficult to reconstruct in precise detail, the major symbols and their underlying conceptual logic remain clear. Overall, the scene closely recreates the Egyptian iconographic motifs shown in the left image. The divine figure (symbol 4), likely representing a local deity, appears to float within a paired or “double” boat (symbol 2) that carries the souls (symbol 5) and holds the cruciform solar emblem (symbol 3). A serpent (symbol 1) coils around the sun and its enclosing square “house,” obstructing the sun’s passage through the underworld. The parallel with the Egyptian myth of the sun’s journey, with the sun and the souls, is evident.

Boat Types in the Negev Desert

Unlike the elaborately carved funerary boats of Egypt or the bird prowed vessels of Scandinavia, Negev ships are rendered in minimal lines, distilling the concept to its essential elements. Their abstraction emphasizes cosmological meaning over representational detail.

Only a limited number of boat motifs have been recorded in the Negev, most of them schematic in form. Their typical inclusion of a single vertical stroke likely reflects the individual nature of burials in the region.

The inverted orientation consistently marks liminality. Across Indo‑European and Near Eastern traditions, inversion signals transition, boundary‑crossing, and entry into non‑ordinary realms. Here it conveys the soul’s descent into darkness before renewal.

Egyptian texts clarify this duality. The Book of the Dead describes two complementary vessels—the Day Barque and the Night Barque—each responsible for carrying the sun and, symbolically, the soul through the full cosmic cycle.

A distinctive Negev subtype boat incorporates the tri‑finger motif. When integrated into the boat’s structure (prow, stern, or mast), this bird foot symbol suggests a vessel capable of crossing both water and sky.

These combined motifs—birds, inverted vessels, and tri‑finger emblems—situate the Negev tradition within a wider Eurasian and Near Eastern symbolic system. Together they express a coherent understanding of the soul’s journey through death toward regeneration.

Conclusion

The rock art from Israel’s Negev Desert offers compelling insight into ancient beliefs about death, renewal, and cosmic order. Ships and boats served as visual metaphors for the most consequential journeys: the sun’s cycle, the soul’s transition, and the journey between earthly and divine realms.

Across continents and millennia, boat imagery expressed humanity’s enduring effort to understand life, death, and the cosmos. In the Negev, these vessels did not cross physical seas; instead, they navigated metaphysical waters, linking earthly life to a larger cosmic order and affirming the hope of rebirth and renewal.

Related reading

Bibliography

Darnell, J. C. (2009). “Iconographic Attraction, Iconographic Syntax, and Tableaux of Royal Ritual Power in the Pre- and Proto-Dynastic Rock Inscriptions of the Theban Western Desert.” Archéo-Nil 19: 83–107.

Golan, A. (1991). Myth and Symbol.

Hornung, E. (1999). The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Cornell University Press.

Huyge, D. (2002). “Cosmology, Ideology and Personal Religious Practice in Ancient Egyptian Rock Art.” In Egypt and Nubia: Gifts of the Desert, ed. R. Friedman, 192–206. London: British Museum Press.

Kaul, F. (1998). Ships on Bronzes: A Study in Bronze Age Religion and Iconography. National Museum of Denmark.

Keel, O., & Uehlinger, C. (1998). Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel.

Kristiansen, K. (2010). “The Sun Journey in Indo-European Mythology and Bronze Age Rock Art.”

Lankester, F. (2012). “Arms-Raised Figures and the Symbolism of Rebirth.”

Lehner, M. (1997). The Complete Pyramids. Thames & Hudson.

Mazar, A. (1992). Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, 10,000–586 B.C.E. Doubleday.

Moran, W. L. (1992). The Amarna Letters. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Redford, D. B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press.

Spence, K. (2000). “Ancient Egyptian Chronology and the Astronomical Orientation of Pyramids.” Nature 408: 320–324.

Zavaroni, A. (2006). “Boat Iconography and the ‘Shades of the Deceased’.”

© All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of negevrockart.co.il.

Yehuda Rotblum