Ancient Egyptian Mythology in Negev Desert Rock Art

The myth of the sun’s journey, depicted in Negev Desert rock art, finds its origin in ancient Egypt. It narrates the sun’s daily voyage from east to west and its perilous descent into the underworld at night. The sun, personified as the god Ra, was believed to travel across the sky by day and navigate the shadowy realm of death after sunset. This nocturnal passage represented the eternal struggle between light and darkness and the victory of order over chaos (Hornung 1999; Wilkinson 2003). From the Book of the Dead, trans. Sir Peter le Page Renouf:

“I look at the sunrise and sunset, the daily return of the day and night, the struggle between light and darkness… in heaven and on earth the sun is the main theme of Egyptian mythology.”

'With Ra as our guide, we traverse the treacherous path of the underworld. The serpent Apophis lurks in the shadows, but Ra’s power and bravery ensure our safe passage. At dawn, we emerge from the underworld, victorious over the darkness, ready to embark on a new journey through the sky'.

Ship Rock Art, Symbolic Interpretation

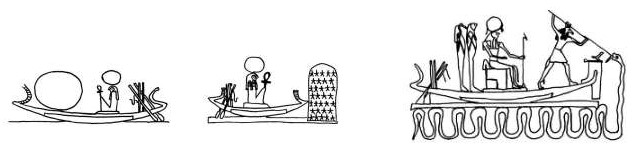

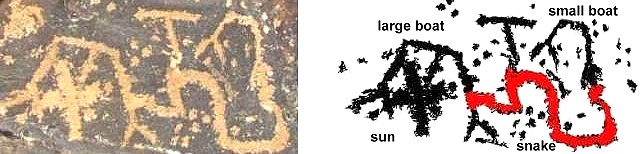

The rock art of the Negev Desert (Fig. 2) portrays two inverted ships that together represent day and night, symbolizing the sun’s complete daily cycle. At first glance, such an interpretation may seem like a considerable imaginative leap. The engravings bear little resemblance to imagery familiar to modern viewers, and their symbolic meaning is not immediately apparent. Yet when viewed through the lens of ancient cosmology, the image gains remarkable coherence. In Egyptian belief, the sun’s journey was explicitly described in sacred texts as a celestial voyage across two worlds—the upper and the underworld. The Book of the Dead and Amduat depict Ra traveling across the sky in his day boat (mandjet) and through the darkness of the underworld in the night boat (mesektet), ensuring the renewal of creation each morning (Hornung 1999; Allen 2005). As stated in the Coffin Texts (Spell 335):

“He sails the sky by day in the bark of millions, and at night he travels through the netherworld in the bark of darkness.”

The shape of the solar bark—slender and gracefully curved at both ends like a swan—was not arbitrary. Its elegant form symbolized the vessel’s ability to navigate both the celestial and the subterranean realms. It mirrored the divine ship seen gliding along the horizon at dawn and dusk, embodying the liminal passage between the worlds of light and darkness.

This imagery explains the symbolic significance of the Negev rock engravings: two inverted vessels of contrasting scale—the larger representing the day bark and the smaller the night bark, which together embody the Egyptian conception of the solar journey through the upper and lower realms. In Egyptian cosmological texts, the maintenance of cosmic order (ma'at) fundamentally depends upon this dual navigation, constituting a perpetual cycle of descent into the netherworld and subsequent regeneration at dawn.

The Negev artist, perhaps inspired by this imagery or by its diffusion across the Near East, distilled the concept into a minimal yet powerful composition. By engraving two simply rendered, inverted ships upon the desert rock, the artist transformed a complex mythological idea into a geometric symbol of cosmic continuity—a visual meditation on the sun’s eternal passage and renewal. Once the symbolic meaning of these motifs is recognized (see Ship and Boat in the Negev Desert), the scene becomes self-explanatory.

The Book of the Dead (ch. 151) explains the meaning of the two ships: “Your right eye is the night lightning of the sun boat; your left eye is the daily lightning of the sun boat.”

A wavy serpent crosses the solar path, attacking the larger ship that carries the sun while at the same time towing the smaller vessel through the underworld. This vivid image captures the myth’s central tension, literally showing the serpent binding the two ships together and reinforcing the connection between light and darkness (Assmann 2001).

The Balance of Forces

In this scene, the sun and its adversary, the serpent, paradoxically cooperate during their nightly encounter. The sun, marked by the cross, embodies the realm of light, resurrection, and cosmic renewal, while the serpent signifies darkness, death, and the underworld. Yet the two are not merely enemies; they are opposing but complementary forces whose interaction preserves its balance. The serpent’s challenge to the sun is not purely destructive—it is a vital part of the sun’s nightly passage and rebirth. In this way, the scene conveys the ancient belief that cosmic order emerges from the tension and harmony between opposing powers that sustain nature’s eternal rhythm (Frankfort 1948; Hornung 1982).

The Negev Desert rock art reflects a local adaptation of this cosmological vision. Through the interplay of paired ships and the serpent, the desert engravers transformed the Egyptian myth of the sun’s perilous voyage into a distinctly regional image of balance and renewal.

Conclusion

The sun’s daily cycle lies at the heart of Egyptian cosmology. Its perpetual rising and setting reaffirm the divine order that governs the world. This eternal rhythm of sun's death and rebirth embodies the harmony between chaos and renewal. In Negev Desert rock art, the same principle is conveyed through paired of ships and a serpent—symbols that echo the sun’s passage across the heavens and through the underworld. The serpent, both destructive and protective, personifies the forces of chaos that the sun must confront each night, yet it also guides and empowers the ships to triumph over these perpetual trials

Related reading

Bibliography

Assmann, Jan. 2001. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Frankfort, Henri. 1948. Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society and Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Hornung, Erik. 1982. Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hornung, Erik. 1999. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Wilkinson, Richard H. 2003. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson.

© All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of negevrockart.co.il

Yehuda Rotblum