The Constellation Hercules

Across the Mediterranean world, the myth of Hercules was inseparable from the seasonal sky. His labors were not abstract adventures but episodes anchored in visible celestial patterns. One of the clearest examples is the hunt of the Stymphalian Birds, a myth consistently linked to the summer heavens, when bird-shaped constellations appear to rise across the sky. The great celestial bird flying along the Milky Way, the constellation Cygnus, was one of them. Hercules appears locked in symbolic tension with these airborne figures, mirroring the heroic confrontation described later in the myth.

The Rock Art Heroes

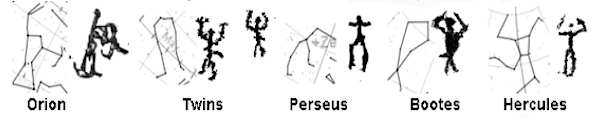

Hercules belongs to a broader class of archetypal heroes that appear repeatedly in myth and rock art: Achilles, Perseus, Bootes, Orion, and the Divine Twins. These figures are not historical individuals but symbolic mediators between worlds. They are portrayed as mortal heroes precisely because they inhabit the threshold between heaven and earth.

The symbolic figures are aligned with constellation shapes, their gestures reflecting their celestial counterparts. Fig. 1 illustrates several such heroic figures from the Negev, each corresponding to a recognizable constellation pattern.

Hercules in the Sky

Hercules is a large but visually restrained northern constellation, lying between Lyra and Corona Borealis, and bordered by Boötes, Draco, Ophiuchus, and Aquila. Unlike royal constellations marked by brilliant stars, Hercules is subdued. Its identity is carried not by brightness but by form and position in the sky. The constellation occupies the middle registers of the sky, neither fully celestial nor fully terrestrial, reflecting his mythic status as a half-god engaged in struggle, endurance, and trial.

Hercules Seasons

Hercules follows a clear seasonal rhythm. From the Negev and the eastern Mediterranean, the constellation becomes visible in the evening sky in late spring, reaches its full dominance during the summer months, and gradually sinks westward as autumn advances. By winter, it disappears entirely, lost in the solar glare. His appearance in the summer marks the season of confrontation and resolution, while his disappearance signals completion. The hero’s work is seasonal, repeating each year as order is restored and chaos subdued.

The Stymphalian Birds Hunt Myth

The Stymphalian Birds episode is the sixth of Hercules’ labors. These vicious birds were devastating the land, killing people and animals. The creatures were said to infest the marshes of Lake Stymphalus in Arcadia, a liminal landscape of reeds and water where no ordinary hunter could pursue them. Their bronze feathers could cut like blades and, in some versions, were launched like missiles, turning the air itself into a weapon.

Hercules could not simply wade into the marsh or shoot blindly into the reeds. Athena, the goddess of wisdom and strategic warfare, supplied him with bronze castanets (krotala) crafted by Hephaestus. When Hercules clashed the castanets at the edge of the lake, their piercing metallic noise startled the birds into flight. Only once they rose into the open sky could he shoot them down with arrows, often said to be tipped with the Hydra’s poison.

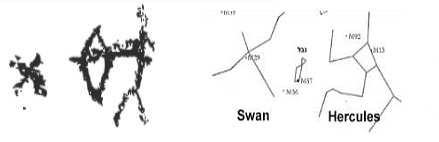

The Hunt scene in Negev Rock Art

In rock art, this episode appears transformed into a cosmological scene. As shown in Fig. 2, the figure identified with Hercules is positioned beside a long-necked bird whose form aligns with the constellation Cygnus. The bird is not depicted as prey on the ground but as an airborne figure, already displaced from the marsh. This reflects the critical moment of the myth: the instant when chaos is forced into visibility and can finally be confronted.

The bird associated with Cygnus is shown elevated, already removed from the ground. Hercules is positioned beside it, not in the act of striking, marking the moment of exposure rather than the outcome.

Conclusion

The Stymphalian Birds episode, viewed through rock art, links the myth to the seasonal constellations of the summer sky. Hercules does not enter the marsh or attack blindly by brute force; instead, he uses a piercing sound to drive the birds from their protected refuge into open space, where they can be confronted. Though famed for his strength, he succeeds through strategy and wisdom.

Bibliography

- Apollodorus. The Library (Bibliotheca), 2.5.6.

- Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica, Book 4.

- Campbell, Joseph. 1949. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Graves, Robert. 1955. The Greek Myths. London: Penguin.

Related reading

© All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of negevrockart.co.il

Yehuda Rotblum