Winter Cosmology in the Negev Rock Art

The Negev Desert is an arid, rain-dependent landscape. All fertility hinges on the timing, distribution, and intensity of the winter rains. When rainfall is sufficient, the desert undergoes a brief but dramatic transformation: plants sprout across the wadis, ephemeral pools collect in rock basins, and ibex and other ungulates enter their birthing season. Without rain, the seasonal renewal does not occur. In such conditions, survival required close attention to environmental cues, including those provided by the night sky (Aveni 2001; Krupp 1997).

Late-Winter Sky in Negev Rock Art

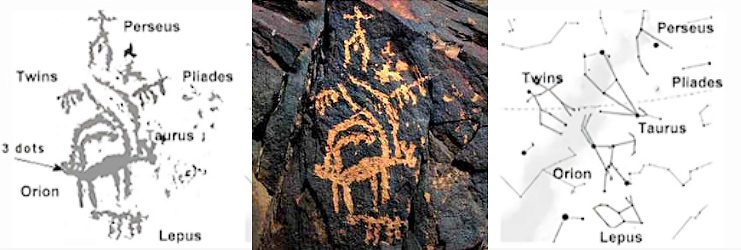

This engraving from Israel’s Negev Desert preserves a band of the late-winter sky in a single composition. At its center stands an ibex whose body outlines the constellation Orion. Above the ibex, sweeping curves render the horns of horns of Taurus, flanked by two characteristic clusters: the compact group of the Pleiades to the right and the V-shaped Hyades near the ibex’s tail. o the left of Orion appears a paired motif consistent with Gemini, and in the upper register an anthropomorphic figure aligns with the position and role of Perseus, marked by the flashing star Algol situated between his bent legs.

Together, these figures form a joyous scene. Perseus lifts his arms in celebration, Orion-ibex anchors the composition, the Twins drift gracefully above, and the Pleiades shine as the season’s promise. Rather than a random assemblage of symbols, the panel functions as a structured celestial calendar linking seasonal change, fertility, and desert life.

When comparing the engraving with with the constellation map in Fig.1, the fidelity is extraordinary. The engraver captured not just individual constellations, but an enormous sweep of the sky, from the region of the North Star down toward the ecliptic. The constellation sequence engraved in the panel corresponds closely to the late-winter sky as it descends toward the western horizon (February–April). This configuration marks the transition from the winter rains to early spring (Hoskin 2001), the most productive interval of the desert year.

For Negev communities, hunters, pastoralists, and small-scale foragers, this was a critical window. The sky served as a rain-sensitive ecological calendar, indicating when to hunt, gather plants, relocate herds, or exploit short-lived water sources. Unlike the fixed agricultural seasons of river civilizations, Negev scheduling had to remain flexible, responding to rainfall variability. The stars did not promise a guaranteed flood; they marked the approach of a possible season of abundance. In this sense, the engraved sky-map expresses both cosmology and practice: knowledge embedded in image and remembered through place (Ingold 2000; Bradley 2000).

Conclusion

Together, these observations suggest that Negev rock art encodes a form of environmental cosmology: celestial movements were read as signals of seasonal behavior, ecological opportunity, and the renewal of life in a rain-dependent desert. By translating the winter–spring sky into stone, artists preserved the timing of the moment when the desert bloomed, animals calved, and human groups mobilized to exploit the year’s brief fertile cycle.

Seen in this light, The engraving is neither random decoration nor purely ritual emblem. It is a material expression of knowledge: a durable mnemonic that fuses sky lore, landscape experience, and survival strategy, an image of the winter gift of life, carved where it could be revisited, taught, and remembered (Aveni 2001; Krupp 1997).

Related reading

Bibliography

Aveni, Anthony F. 2001. Skywatchers: A Revised and Updated Version of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Belmonte, Juan Antonio, and Josep Lull. 2023. Astronomy of Ancient Egypt: A Cultural Perspective. Cham: Springer.

Bradley, Richard. 2000. An Archaeology of Natural Places. London: Routledge.

Dibon-Smith, Richard. 1990–2012. Constellations and Ancient Mythology (online resource).

Golan, Ariel. 1991. Myth and Symbol: Symbolism in Prehistoric Religions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoskin, Michael. 2001. Tombs, Temples and Their Orientations: A New Perspective on Mediterranean Prehistory. Bognor Regis: Ocarina Books.

Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge.

Krupp, E. C. 1997. Skywatchers, Shamans & Kings: Astronomy and the Archaeology of Power. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Rappenglück, M. (2015). “Palaeolithic Skyscapes.” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry. (Rock art and celestial cognition.)

Zohar, I., & Dayan, T. (1998). “Animal Exploitation in the Negev.” Journal of Arid Environments. (Ecological context for ibex behavior.)

© All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of negevrockart.co.il

Yehuda Rotblum