Ancient Moon Calendars in Negev Desert Rock Art

Creative calendars that follow the Moon’s cycles, Negev Desert rock art

Rock art served as a crucial medium for recording and transmitting knowledge. In the Negev Desert, engravings reveal that ancient communities used symbolic marks to track the lunar cycle. These petroglyphs—ranging from elaborate calendar systems to simple arrays of dots and lines demonstrate an early attempt to organize time according to celestial rhythms (Ruggles 2015).

The Negev Desert, in southern Israel, covers roughly 13,000 square kilometers (about 60% of Israel’s territory). Its dry climate has preserved an exceptional archaeological record. Among these remains, rock engravings provide unique evidence of how early societies observed the heavens and translated astronomical knowledge into practical timekeeping systems.

Early Moon Calendars

The use of lunar calendars can be traced back at least 20,000 years (Marshack 1972). These systems enabled early communities to regulate agricultural work, ritual observances, and social gatherings by following the phases of the moon. Across cultures, the moon became associated with fertility, renewal, and cyclical order (Aveni 2001;).

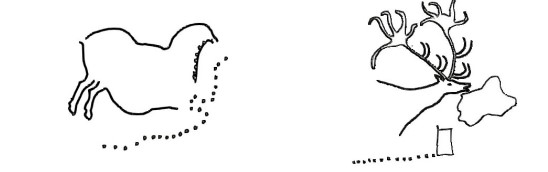

One well-known example comes from Lascaux Cave in France (c. 15,000 BCE). Beneath a pregnant animal, 28 dots have been interpreted as lunar-day notations (Marshack 1991). The connection between fertility imagery and lunar counting illustrates how symbolic art intertwined cosmological observation with the rhythms of human life.

Fig.1 illustrates an ancient lunar calendar from the Lascaux Cave dated 15,000 BC. Under the pregnant four-legged animal are twenty-eight dots, each representing a day in a lunar cycle. The animal pregnancy symbolizes renewal, the same quality inherent in the moon cycle. On the right side under the deer, there is a square with thirteen dots, representing the number of crescent moon nights for half the moon cycle. The count proceeds in both directions forming twenty-six days, the number of days the Moon appears in the sky. The square is a "rest station" that marks the moonless days.

This Paleolithic calendar demonstrates sophisticated astronomical observation. The artists at Lascaux understood not only the basic lunar cycle but also the symbolic connection between fertility, renewal, and celestial movements. The precision of the dot counting system suggests that moon observation was a systematic practice rather than casual sky-watching.

Rock Art Moon Calendars from Negev Desert

The lunar month averages 29.5 days, with the moon visible for about 28. A striking engraving from the Negev Desert (Fig. 2) resembles a centipede with twenty-eight legs ending in a square. Each leg marks a single day, while the square signifies the moon’s disappearance at the close of the cycle. This device parallels the counting principle seen in the Lascaux example, pointing to a shared symbolic approach to lunar reckoning.

The centipede design represents an imaginative method of tracking the lunar cycle. Its many legs and segments provided a natural model for tallying days, transforming a non-existent ordinary creature into a symbolic calendar. In this engraving, the twenty-eight legs correspond to the visible days of the moon, and when all legs have been counted, the cycle is complete. The square covering the final leg symbolically marks the moon’s vanishing at the end of the month. The rock art was utilized as follows:

- Each leg could be marked with a small stone or other marker at night

- Users could see at a glance how many days had passed

- The square endpoint clearly marked when to restart counting

- Functioned during cloudy nights when moon observation was impossible

Sin Moon Calendar, Negev Desert

Mesopotamian influence also reached the Negev. One panel (Fig. 3) shows a seated figure closely resembling Sin, the Sumerian moon-god, as depicted in cylinder seals. His image appears in the center of Fig. 3, complete with the characteristic headdress and chair, with one hand extended toward a crescent moon above. In the rock art, above the figure, 14 engraved lines function as a lunar tally: stones could be placed and then removed each day to follow the waxing and waning phases. This system reflects the transmission of Mesopotamian calendrical traditions into local desert contexts (Black & Green 1998; van der Toorn 1996).

Star Moon Calendar, Negev Desert

Another Negev engraving (Fig. 4) depicts two seven-rayed star motifs used as lunar cycle counters. The count begins with the ray beneath the engraved crescent, a sliver of the moon, where stones were added daily until the first star was filled, then continued on the second. After 14 days (half a lunar cycle), the stones were removed in reverse order to mark the waning phase.

At the bottom left of the rock art are four engraved lines, each denoting a week of seven days. This simple feature helped viewers track the current week within the lunar cycle. (Kelley & Milone 2011)

Conclusion

The Negev engravings provide compelling evidence for the early development of lunar calendars. These systems demonstrate remarkable ingenuity, producing weather-independent, calendars the regulated agricultural, social, and ritual life. With only lines, dots, and symbolic figures, desert societies succeeded in recording the passage of time without direct sky-watching (Ruggles 2015).

The integration of Mesopotamian influences, such as the Sin calendar, with indigenous innovations highlights the Negev’s role as a cultural crossroads. These lunar records embody both technical achievement and humanity’s enduring need to structure life in harmony with celestial cycles (Kelley & Milone 2011;).

Related reading

Bibliography

Aveni, Anthony. Skywatchers. University of Texas Press, 2001.

Black, Jeremy & Green, Anthony. Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. British Museum Press, 1998.

Kelley, David & Milone, Eugene. Exploring Ancient Skies: A Survey of Ancient and Cultural Astronomy. Springer, 2011.

Marshack, Alexander. The Roots of Civilization. McGraw-Hill, 1972; rev. ed. Moyer Bell, 1991.

Ruggles, Clive. Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy. Springer, 2015.

Van der Toorn, Karel. Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria and Israel. Brill, 1996.

© All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of negevrockart.co.il

Yehuda Rotblum